Ji Tan *, Yangyan Sun, Daoyuan Wang

Department of Gynaecology, Jiangyin Hospital, Medical school of Southeast University, Jiangyin City. Jiangsu Province, PR China

BACKGROUND To compare the operative data and early postoperative outcomes for myomectomy performed by isobaric gasless laparoscopically with those by minilaparotomy (MLT) isobaric gasless laparoscopy (LA) in a series of patients with large uterine leiomyomas (≥5cm).

METHODS 80 patients were randomized using a computer randomization list to LA (n = 40) or MLT (n = 40) group.

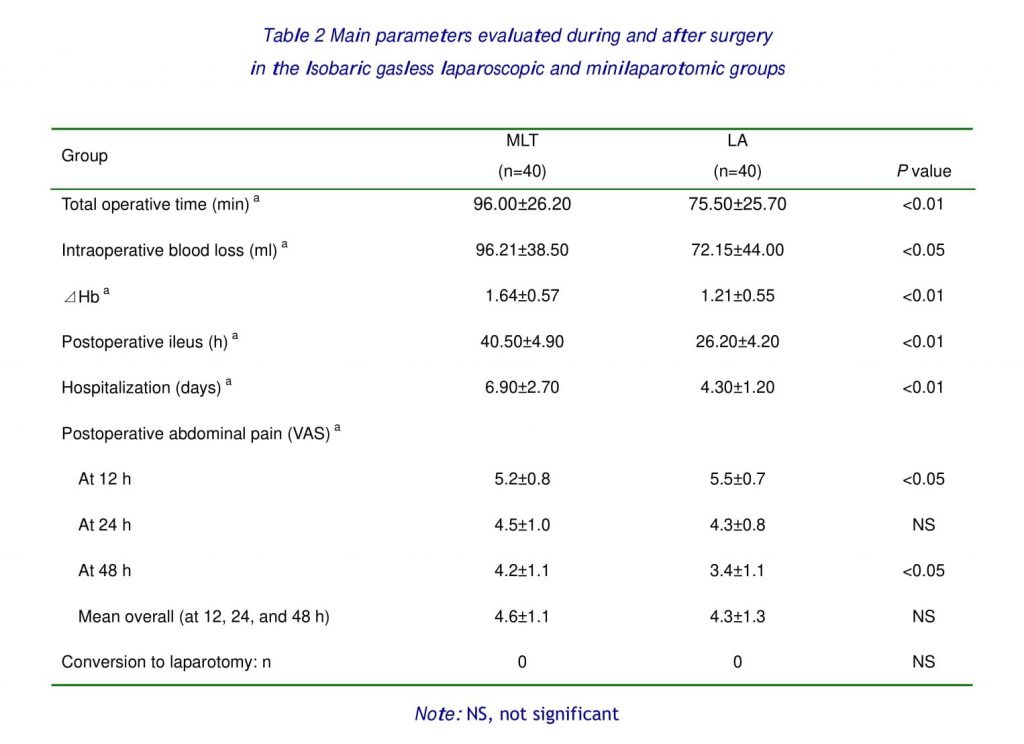

RESULTS The mean operating time was significantly shorter after LA than after MLT (75.50±25.70 vs 96.00±26.20 min; p < 0.01). The intraoperative blood loss was less with LA (72.15±44.00 vs 96.21±38.50 ml; p < 0.05), and ⊿ Hb was less with LA (1.21±0.55 vs 1.64±0.57; p < 0.05). The postoperative ileus was shorter after LA than after MLT (26.20±4.20 vs 40.50±4.90 hours; p < 0.01). The mean VAS score at 12 h for abdominal pain was 5.5±0.7 in the LA group and 5.2±0.8 in MLT group (p< 0.05), whereas there were no differences in the two groups at 24 h, and at 48h.

CONCLUSIONS Several operative and immediate postoperative outcomes were significantly better in the gasless LA group than in the MLT group.

KEY WORDS Isobaric gasless Laparoscopy; Minilaparotomy; Myomectomy

INTRODUCTION

Uterine leiomyomas (fibroids or myomas) are benign clonal tumours that arise from the smooth-muscle cells of the human uterus. They are clinically apparent in about 25% of women (1), and with new advanced imaging techniques, the true clinical prevalence may be higher. Careful pathological examination of surgical specimens suggests that the prevalence is as high as 77% (2).

Most myomas cause no symptoms, but many women have significant symptoms warranting therapy. Symptoms attributable to myomas can generally be classified in three distinct categories: abnormal uterine bleeding, pelvic pressure and pain, and reproductive dysfunction (3).

Myomectomy is advisable for women who are willing to preserve their childbearing capabilities and it is necessary when myomas are either growing rapidly and causing infertility/recurrent abortion though asymptomatic, or symptomatic manifested by abnormal uterine bleeding or pain (1,4,5).

Laparoscopy has developed into an effective tool that facilitates a wide range of pelvic surgery, including conservative myomectomy. The most common motive for conservative myomectomy, and hence laparoscopic myomectomy, is the patient’s will to avoid hysterectomy for personal reasons, or conserve fertility.

Among the minimally invasive approaches to myomectomy, isobaric gasless laparoscopy (LA), using an abdominal wall–lifting device (6,7), minilaparotomy (MLT) (8-10) and laparoscopically assisted minilaparotomy (LA-MLT) (11) have been introduced recently.

It is reported that myomectomy by isobaric gasless laparoscopy is feasible and safe, and it appears to have been several advantages over conventional laparoscopy with pneumoperitoneum (12, 13).

Myomectomy via minilaparotomy has been proved to be a safe and effective minimally invasive approach to myomectomy. Early discharge and recovery to normal activities were comparable with those for conventional laparoscopy, and this approach is far more cost effective (10).

However, no study compares LA with MLT myomectomy for removal of large uterine leiomyomas. Even there are several studies of laparoscopic myomectomy for large myomas (6,13,16), or compares with abdominal myomectomy (17).

Therefore, we undertook the first randomized study comparing the operative data and early postoperative outcome for myomectomy performed by isobaric gasless LA compared with those for MLT in a series of patients with large uterine leiomyomas (≥5cm) randomly assigned to each surgical technique.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Equipment and Apparatus

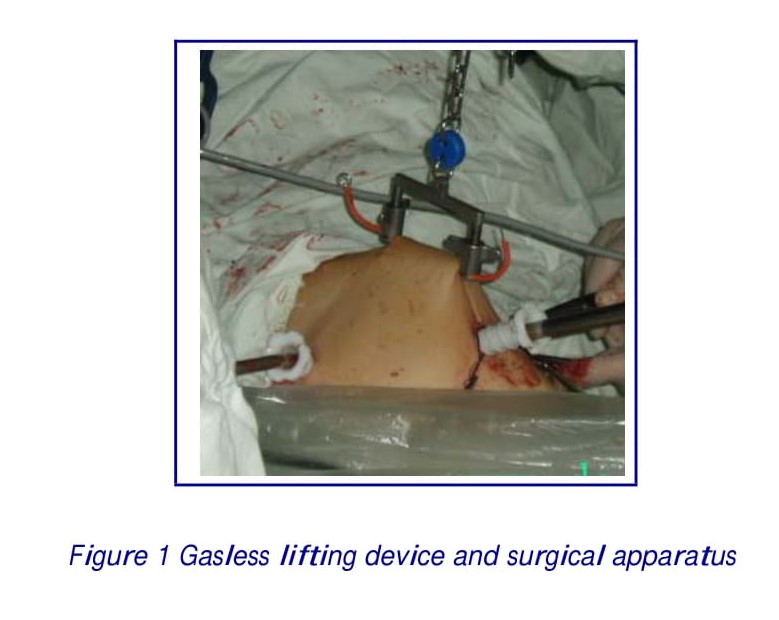

Video electronic laparoscope (Japan Olympus Co.) and gasless lifting device and surgical apparatus (Japan Daoke Co.). In gasless surgical apparatus, the length was between that of laparotomy and laparoscopic surgical apparatus, there was insulating layer in other parts besides forceps tip, and incision protective sleeve was made of plastic gel material (Fig.1)

Patient Selection

The trial was performed in the Department of Gynaecology, Jiangyin Hospital, affiliated to Southeast University, Jiangsu Province, China. The study was previously approved by the local ethics committee. From January 2006 to October 2007, all women with symptomatic uterine myomas requiring myomectomy were considered eligible for the study. The criteria for inclusion in the study specified the presence of one to three symptomatic intramural or subserosal myomas (without peduncle) associated with either infertility or fast growth and having a diameter of 5 to 10 cm.

Major medical conditions, psychiatric disorders, current or past history of acute or chronic physical illness, premenstrual syndrome (18, 19), current or past (a washout period of at least 6 months was considered appropriate before enrolment) use of hormonal drugs or drugs influencing cognition, vigilance, or mood, inability to complete the daily diary, and a history of alcohol abuse were all considered as exclusion criteria.

In addition, the following specific exclusion criteria were included: no desire to conceive, hypoechoic or calcified leiomyomas diagnosed at ultrasound (20), presence of submucosal leiomyomas or alterations of the uterine cavity screened by hysteroscopy and of other uterine or adnexal abnormalities at ultrasound (e.g., adenomyosis, abnormal endometrial thickness), pattern of hyperplasia with cytological atypia in the endometrial biopsy performed for abnormal uterine bleedings under hysteroscopy on suspected areas, an abnormal Papanicolaou smear, and a positive urine pregnancy test.

Lastly, symptomatic women who did not have a previous conception resulting in a live baby or with a tubal/male factor subfertility were also excluded.

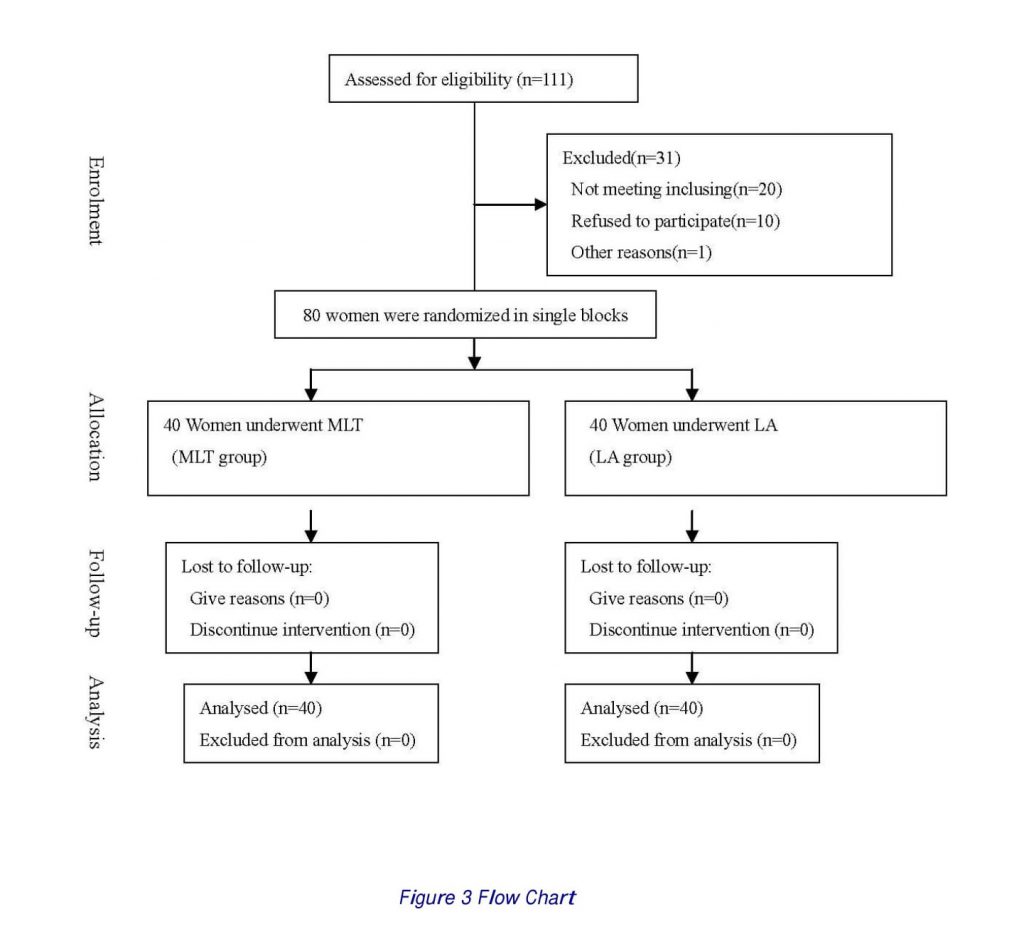

Of the 111 women requiring myomectomy, 91 fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were recruited for the trial. A written informed consent was obtained from each patient before randomization. The enrollment was closed when 80 patients were included, and 40 patients were allocated to each group (Fig.3).

Study Design

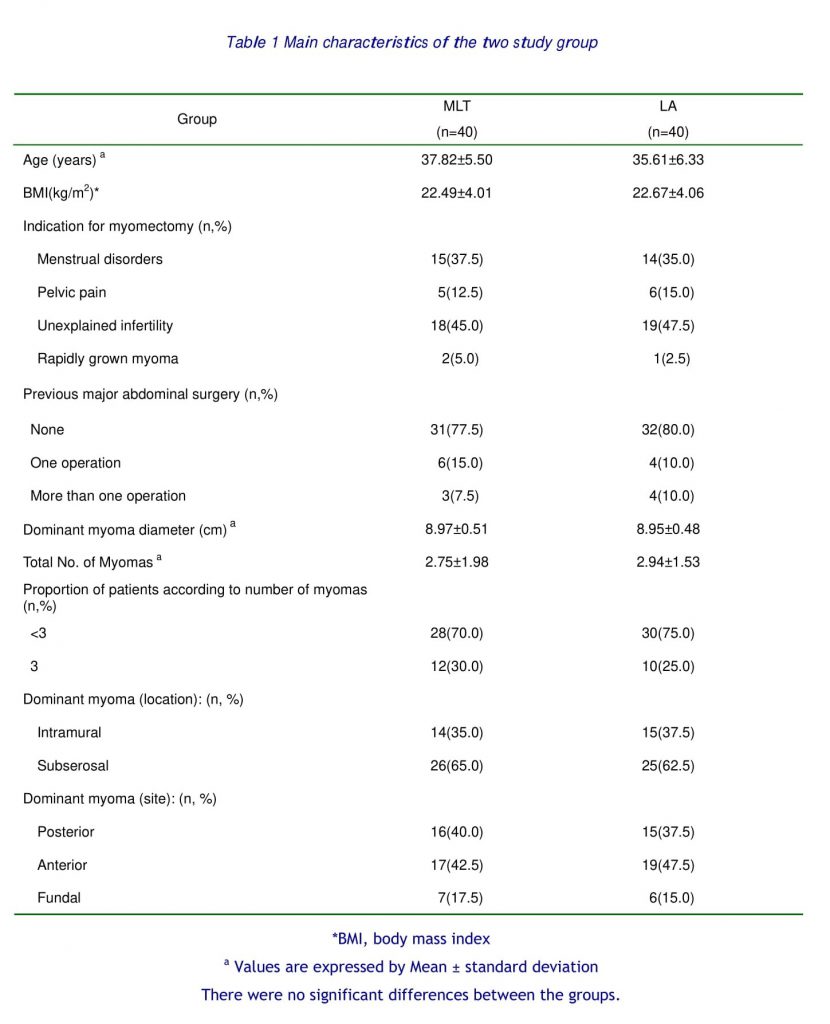

At study entry, age, parity, and body mass index (BMI), leiomyoma-related symptoms, previous laparotomies, and associated medical conditions were assessed in each patient by the same clinician.

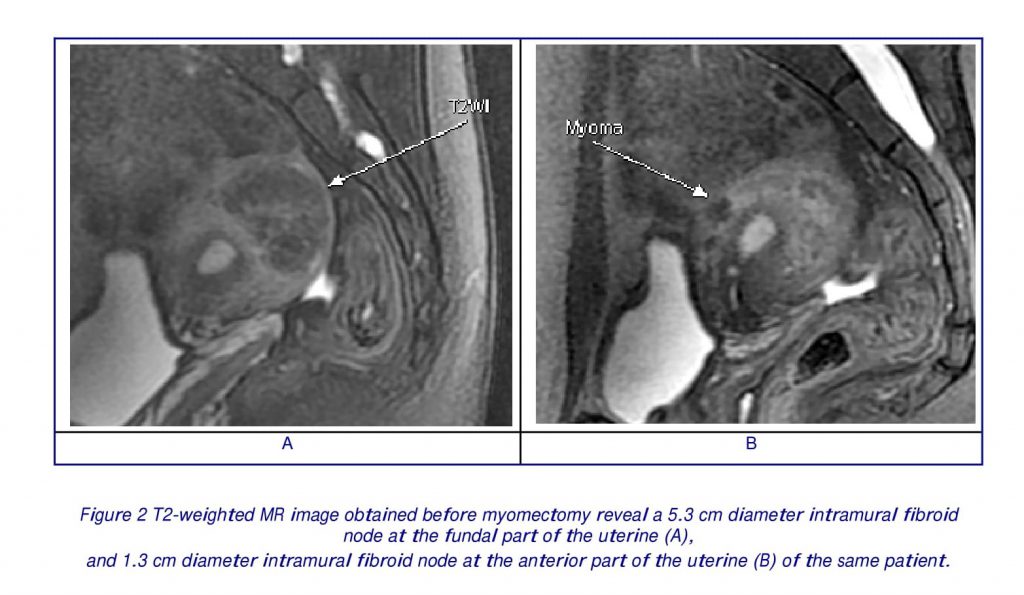

All ultrasound examinations were performed transvaginal by an experienced operator, who assessed the presence/absence of associated pelvic diseases, evaluated uterine dimensions, and leiomyoma number, dimension, and location. And conventional T1- and T2-weighted magnetic resonance (MR) images were performed in all patients before myomectomy, to confirm the ultrasound examination results, especially to confirm the numbers and location of leiomyomas (Fig 2).

At study entry, a sample of venous blood was obtained from each patient between 8 and 9 AM, after an overnight fast and bed rest during the early proliferative phase (second to third day of the cycle) to evaluate a complete blood count.

Each woman gave her informed consent to be included into the study, which was previously approved by the local ethics committee. After enrolment by a physician, each woman was randomized blindly by a nurse to LA (n = 40), or MLT (n = 40), in closed and dark-colored envelope until surgeries were assigned (before entering in the operating room), using a computer-generated list of randomizations. Thus, patients were assigned to one of the two surgical procedure groups (i.e., LA or MLT). The same surgeons performed all surgical procedures.

During each surgical procedure, total operative time. Specifically, the total duration time of the surgical procedure was calculated during the LA or LA-MLT procedure beginning from abdominal skin incision, before Verres needle insertion, to skin suture.

Intraoperative blood loss, intraoperative and postoperative complications were also evaluated and recorded in both groups. The intraoperative blood loss was differentially expressed as the difference between aspirated and irrigated liquid, and as hemoglobin level decrease (⊿ Hb). Intraoperative complications were defined as laparotomic conversions, and as bowel, bladder, ureteral, or vascular injuries. Laparotomic conversions were defined as open abdominal access through a more than 7-cm long skin incision.

After intervention all patients received an IV bolus of tramadol (100 mg), followed by patient-controlled analgesia (tramadol 200 mg [2 vials] in 500 mL of saline solution) (21). The postoperative analgesia was administered during the first 12 hours after surgery. At the end of the surgical procedures the postoperative pain was also evaluated using VAS. The VAS consisted of a non-graduated 10 cm line ranging from ‘no pain’ to ‘pain as bad as it could be’ (22). Postoperative pain was specifically assessed in each group at 12, 24 and 48 hours after the surgical procedure.

Women were allowed to eat and drink the morning after surgery, and to ambulate as soon as they felt comfortable. The urinary catheter was removed the evening of the surgery. A blood sample was obtained and ⊿ Hb was calculated for each woman 24 hours after surgery.

Duration of postoperative ileus and hospitalization were evaluated in both groups. Hospitalization time was defined from entry (the day of surgery) to discharge.

Surgical Procedures

All Procedures were performed by the same surgeons (Dr. Ji Tan, M.D.) using the same technique. The operator was informed on the type of intervention to perform (if LA or MLT) just before entering the operating room. A drug for thrombosis prophylaxis was not administered to any patient. After anesthesia administration, each patient was placed in a modified lithotomic position. Immediately before surgery, each patient received 2 g of IV cephalosporin as antibiotic prophylaxis, and if necessary, a same dose was repeated if the intervention lasted more than 2 hours.

Laparoscopic Myomectomy (LA)

In the LA group, after anesthetizing, lie at position for vesical-calculus incision, lower head 35°and lift hip, and lift uterus for easy exposure of uterine myoma. Incise umbilical opening, put 10mm Troca, insert laparoscope, pass vertically Kirschner’s needle (diameter: 2 mm) through subcutaneous tissue of lower abdomen at an interval of 10cm, suspend both ends of steel needle at cross arm of lifting/pulling device via saddle chain, connect cross arm with vertical arm, fix at one side of operating table. Incise 1.5-2.0 cm hole to peritoneum at left lower abdomen, put incision protective sleeve via this hole, and start apparatus operation. Excise myoma one by one according to its growing position. 1) Subserosal fibroid: Broad tumor area unable for complete exposure, inject jointly 20U oxytocin+20ml normal saline (or 6U pituitrin+20ml normal saline) at tumor pedicle, excise in ring shape along tumor pedicle, and tear off myoma by clamping with grabbing forceps. Active hemorrhage in wound: stop bleeding through electrocoagulation, suture in 8-shape with #1 micro-bridge suture. Subserosal fibroid with narrow pedicle: coagulate electrically directly (or ligate tumor pedicle with wire), and then excise myoma. 2) Intramural fibroid: inject the diluted oxytocin or pituitrin between myoma and myometrium so as to reduce bleeding during the operation, coagulate electrically protruded myoma surface, incise myometrium and myoma capsule until exposure of tumor body, clamp tumor body with grabbling forceps, push uterus tissue and tumor body pseudocapsule downwards with curved forceps until complete tearing of tumor body, stitch submucous muscle layer and cervical muscle layer with #1 absorbable catgut suture layer by layer in case intramural fibroid protruding into uterus cavity (or larger deeper myoma cavity), and stitch first uterus incision continuously and then muscular layer through once pressing/embedding in case of intramural fibroid not protruding into uterus cavity.

Minilaparotomic Myomectomy

In the minilaparotomic group, all procedures were performed without laparoscopic assistance. A 4 to 7cm transverse incision was performed for minilaparotomic access. To avoid accidental extension of the minilaparotomies two double sutures were made at the end of the skin incisions. The length and the distance from pubic symphysis of the skin incision varied according to leiomyoma dimension and localization.

In both groups (LA and MLT), the uterine incision was performed using the same electrosurgical device with a cutting current of 70 W. At the end of each intervention, the pelvis was washed with saline solution. No adhesion barrier or saline dextran macromolecular solutions were left in the peritoneal cavity. All operative samples were submitted for pathologic examination.

No peritoneal or incisional instillation of topical analgesics is used in laparoscopy procedures. For the first 12h after surgery, each subject receives an i.e., analgesic therapy. Analgesics consist of ketoprofen (45 mg/12h) and tramadol (150mg/12h). Thereafter, analgesics are suspended and administered only on a patient’s demand.

Statistical Analysis

A power calculation verified that more than 40 patients in each group would be necessary to detect a difference of more than 48h in discharge time with an alpha error level of 5% and a beta error of 80%. Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Program/SPSS for Windows, version 11.5 (Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous outcome variables were analyzed using Student’s t-test. Discrete variables were analyzed with the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Figure 3 illustrates the flow diagram of the present clinical study. The two groups of 40 patients each were obtained from randomization of 80 patients (Fig. 3).

No difference was observed between the two groups in uterine size, dimension of leiomyomas, main dimension of the largest leiomyoma, and number of leiomyomas (Table 1). The localization of leiomyomas was also similarly distributed in the two groups (Table 1). In all cases the estimated size and the histologic leiomyomas diagnosis, suspected before surgery through ultrasound and MR imaging, were confirmed, respectively, by macroscopic and microscopic examination of the enucleated tumors. Procedures were successfully performed for all the patients in both groups.

Table 2 shows the operative parameters in the two groups. The mean operating time was significantly shorter after LA than after MLT (75.50±25.70 vs 96.00±26.20 min; p < 0.01). The intraoperative blood loss was less with LA (72.15±44.00 vs 96.21±38.50 ml; p < 0.05), and ⊿ Hb was less with LA (1.21±0.55 vs 1.64±0.57; p < 0.05). No intraoperative complications occurred, and no case was returned to the theater in either group. No conversion to standard laparotomy was necessary. The hospitalization days was shorter after LA than after MLT (4.30±1.20 vs 6.90±2.70 days; p < 0.01). The postoperative ileus was shorter after LA than after MLT (26.20±4.20 vs 40.50±4.90 hours; p < 0.01).

The mean VAS score at 12h for abdominal pain was 5.5±0.7 in the LA group and 5.2±0.8 in MLT group (p< 0.05), whereas it was analogous in the two groups at 24h, and at 48h, was 3.4±1.1 in the LA group and. 4.2±1.1 in the MLT group (p< 0.05). And no difference between two groups was detected in mean overall (at 12, 24 and 48h).

DISCUSSION

Historically, there has been little innovation in treatment for fibroids, nominally because they are benign and cause morbidity, not mortality, and because leiomyoma research is underfunded compared with other non-malignant diseases. Medical therapy for fibroids is limited too. The only FDA approved medical therapy is a GnRH agonist used preoperatively with iron. GnRH agonists abrogate both bleeding and bulk-related symptoms but induce significant menopausal side effects that limit therapy. Tumors also rapidly regrow if not removed surgically. The standard treatment of uterine fibroids – surgical excision and hysterectomy – has been promulgated as the one-size-fits-all solution (23).

However, myomectomy is advisable for women who wish to preserve their childbearing capabilities and it is necessary when myomas are either growing rapidly and causing infertility/recurrent abortion though asymptomatic, or symptomatic manifested by abnormal uterine bleeding or pain (1,4,5).

Laparoscopy has developed into an effective tool that facilitates a wide range of pelvic surgery, including conservative myomectomy. The most common motive for conservative myomectomy, and hence laparoscopic myomectomy, is the patient’s will to avoid hysterectomy for personal reasons, or conserve fertility.

Among the minimally invasive approaches to myomectomy, isobaric gasless laparoscopy (LA), using an abdominal wall–lifting device (6,7), minilaparotomy (MLT)(8-10) and laparoscopically assisted minilaparotomy (LA-MLT)(11) have been introduced recently.

It is reported that myomectomy by isobaric gasless laparoscopy is feasible and safe, and it appears to offer several advantages over conventional laparoscopy with pneumoperitoneum (12,13).

Retrospective studies have shown isobaric gasless laparoscopy to be a feasible, reproducible, reliable, safe procedure for removing intramural and subserosal myomas (6,7). Moreover, gasless laparoscopic myomectomy permitted the removal of large intramural myomas through a minimal access procedure with satisfactory results (12,13). Therefore, it was suggested that gasless laparoscopic myomectomy could be indicated primarily for removal of large intramural myomas or for multiple myomectomies (≥3 myomas per patient). The use of minilaparotomy in surgery for benign gynecologic disease has been well established (8). Laparoscopic assisted myomectomy was first reported in 1994 (24). In their review of 57 cases, the authors concluded that the use of the minilaparotomy incision is a safe alternative to myomectomy by laparotomy. It is technically less difficult to perform than laparoscopic myomectomy, allows better closure of the uterine defect, and may require less time to perform. The procedure is far easier to teach than laparoscopic myomectomy because of the high degree of technical skill required for the latter.

Similarly, myomectomy via minilaparotomy was shown to be a safe and effective minimally invasive approach with little bleeding, few complications, and early discharge and return to normal activities (8,9,10,25).

In two retrospective non-randomized studies, LAMLT induced a similar blood loss, but fewer days of hospitalization, fewer days to resume normal activity (24,26) and less post-operative use of analgesics (26).

The first randomized study reporting that MLT and LA-MLT offer advantages in comparison with classic laparotomy (11). To the best of our knowledge, only two prospective trials in the literature compare myomectomy with MLT and conventional LA using CO2 (14,15), only one study compares MLT with isobaric gasless LA myomectomy, and only one study compares laparotomy (LT), MLT with LA-MLT. However, no study compares LA with isobaric gasless LAMLT myomectomy for removal of large uterine leiomyomas. Even there are several studies of laparoscopic myomectomy for large myomas (6,13,16), or compares with abdominal myomectomy (17).

Therefore, we undertook the first randomized study comparing the operative data and early postoperative outcome for myomectomy performed by isobaric gasless LA compared with those for MLT in a series of patients with large uterine leiomyomas (≥5cm) randomly assigned to each surgical technique.

In our study, the operation was completed for all the patients using a minimally invasive approach (gasless laparoscopy or minilaparotomy), and no conversion to standard laparotomy was necessary. No case in either group was returned to the operative theater. The mean VAS score at 12h for abdominal pain in the MLT group was less than in LA group, whereas it was analogous in the two groups at 24h. And no difference between two groups was detected in mean overall (at 12, 24 and 48h). And the intraoperative blood loss, ⊿ Hb, hospitalization days and postoperative ileus were shorter in LA group than MLT group.

The rate of conversion to open surgery for laparoscopic myomectomies has been reported between 3.3 and 28.7% (27,28). The main reason for conversion is the need to control heavy bleeding (27,29), which is greatly influenced by an accurate and quick suture. Moreover, the high number of myomas, the intramural type, the large size and the location have been related to a higher risk of conversion.

All cases with large myomas in both groups in our study, however, no intra-operative complications were observed, and no patients were submitted to a second surgery for early post-operative complications. The role of MR imaging before myomectomy is one of important factors. Despite its relatively high cost, MR imaging is a non-invasive procedure that allows the diagnosis of leiomyomas to be established with a great degree of confidence and affects patients’ treatment by reducing the number of unnecessary surgeries (30). This reduction presumably may lead to a considerable reduction in health care expenditures. MR imaging can assist in preoperative planning for myomectomy by enabling accurate detection and localization of individual tumors (Fig 2). Conditions that mimic leiomyomas at physical examination and US can be characterized with MR imaging (31). And magnetic resonance imaging was helpful in preoperative planning and performing an uncomplicated abdominal myomectomy during pregnancy, respectively (32).

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that isobaric gasless LA and MLT can be a suitable option in uterine myomectomy. Several surgical and immediate postoperative outcomes were significantly better in the gasless LA group than in the MLT group. However, multi-center prospective randomized studies are required to confirm the results of this study, and to compare early and late clinical outcome of myomectomy by MLT with that performed by LA, including but not limited to recurrence rate, fertility, and obstetric outcome.

REFERENCE

1. Buttram VC Jr, Reiter RC. Uterine leiomyomata: etiology, symptomatology, and management. Fertil Steril 1981; 36: 433-45.

2. Cramer SF, Patel A. The frequency of uterine leiomyomas. Am J Clin Pathol 1990; 94: 435-38.

3. Elizabeth A Stewart. Uterine fibroids The Lancet 2001; 357:293-298.

4. Vollenhoven B.J., Lawrence A.S., Healy D.L. Uterine fibroids: a clinical review. Br. J. Obstet. Gynecol 1990; 97:285-298.

5. Donnez J., Mathieu P.E., Bassil S., Smets M., Nisolle M., Berliere, M. Fibroids: management and treatment: the state of the art. Hum. Reprod. 1996; 11: 1837-1840.

6. Chang FH, Soong YK, Cheng PJ, Lee CL, Lai YM, Wang HS, Chou HH. Laparoscopic myomectomy of large symptomatic leiomyoma using airlift gasless laparoscopy: a preliminary report. Hum Reprod 1996; 11:1427-1432

7. Damiani A, Melgrati L, Marziali M, Sesti F. Gasless laparoscopic myomectomy: indications, surgical technique, and advantages of a new procedure for removing uterine leiomyomas. J Reprod Med 2003; 48: 792-798

8. Benedetti-Panici P, Maneschi F, Cutillo G, Scambia G, Congiu M, Mancuso S. Surgery by minilaparotomy in benign gynecologic disease. Obstet Gynecol 1996; 87: 456-459

9. Fanfani F, Fagotti A, Longo R, Marana E, Mancuso S, Scambia G. Minilaparotomy in the management of benign gynecologic disease. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2005; 119:232-236

10. Glasser MH. Minilaparotomy myomectomy: a minimally invasive alternative for the large fibroid uterus. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2005; 12: 275-283

11. Cagnacci F, Pirillo D, Malmusi S, Arangino S, Alessandrini C, Volpe A. Early outcome of myomectomy by laparotomy, minilaparotomy and laparoscopically assisted minilaparotomy. A randomized prospective study. Human Reproduction 2003; 18: 2590-2594.

12. Damiani A, Melgrati L, Marziali M, Sesti F, Piccione E. Laparoscopic myomectomy for very large myomas using an isobaric (gasless) technique. JSLS 2005; 9: 434-438

13. Damiani A, Melgrati L, Franzoni G, Stepanyan M, Bonifacio S, Sesti F. Isobaric gasless laparoscopic myomectomy for removal of large uterine leiomyomas. Surg Endosc 2006; 20: 1406-1409

14. Fanfani F, Fagotti A, Longo R, Marana E, Mancuso S, Scambia G. A prospective study of laparoscopy versus minilaparotomy in the treatment of uterine myomas. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2005; 12: 470-474

15. Alessandri F, Lijoi D, Mistrangelo E, Ferrero S, Ragni N. Randomized study of laparoscopic versus minilaparotomic myomectomy for uterine myomas. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2006; 13: 92-97

16. Yoon HJ, M.S. Kyung, U.S. Jung, et al. Laparoscopic Myomectomyfor Large Myomas. J Korean Med Sci 2007; 22: 706-12.

17. Seracchioli R., Rossi S., Govoni F., Rossi E., Venturoli S., Bulletti C., Flamigni C… Fertility and obstetric outcome after laparoscopic myomectomy of large myomata: a randomized comparison with abdominal myomectomy. Human Reproduction. 2000; 15: 2663-2668.

18. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994.

19. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M, Willams JBM. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID), Clinician Version: User’s Guide. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Press, 1996.

20. Zullo F, Pellicano M, De Stefano R, Zupi E, Mastrantonio P. A prospective randomized study to evaluate leuprolide acetate treatment before laparoscopic myomectomy: efficacy and ultrasonographic predictors. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1998;178: 108 -112.

21. Zullo F, Palomba S, Corea D, Pellicano M, Russo T, Falbo A, et al. Bupivacaine plus epinephrine for laparoscopic myomectomy: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2004; 104: 243–249.

22. Vassiliou MC, Feldman LS, Andrew CG, Bergman S, Leffondre K, Stanbridge D, et al. A global assessment tool for evaluation of intraoperative laparoscopic skills. Am J Surg 2005; 190: 107-113.

23. Cheryl Lyn Walker, Elizabeth A. Stewart. Uterine Fibroids: The Elephant in the Room. Science.2005; 308: 1589-1592

24. Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Bess O. Laparoscopically assisted myomectomy: a report of a new technique in 57 cases. Intl J Fertil & Menop Studies 1994;39: 39-44.

25. Pelosi MA II, Pelosi MA III. Pelosi minilaparotomy hysterectomy: a non-endoscopic minimally invasive alternative to laparoscopy and laparotomy. Surg Technol Int 2004; 13: 157-167

26.Goldberg J.M., Falcone T., Amundson B., Bradley L. Laparoscopic assisted versus abdominal myomectomy. Fertil. Steril 1999; 71(Suppl.1), 8S.

27. Darai E, Dechaud H, Benifla JL, Renolleau C, Panel C, Madelenat P. Fertility after laparoscopic myomectomy: preliminary results. Hum Reprod 1997; 12: 1931-1934.

28. Landi S, Zaccoletti R, Ferrari L, Minelli L. Laparoscopic myomectomy: technique, complications, and ultrasound scan evaluation. J Am Ass Gynecol Laparosc 2001; 8: 231–240.

29. Seinera P, Arisio R, Decko A, Farina C, Crana F. Laparoscopic myomectomy: indications, surgical techniques, and complications. Hum Reprod 1997; 12: 1927-1930.

30.Mark C. Alanis, Avick Mitra, Nikki Koklanaris. Preoperative Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Antepartum Myomectomy of a Giant Pedunculated Leiomyoma. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2008; 111: 577-579.

31.Weinreb JC, Barkoff ND, Megibow A, Demopoulos R. The value of MR imaging in distinguishing leiomyomas from other solid pelvic masses when sonography is indeterminate. AJR 1990; 154: 295-299

32. Murase E,Siegelman ES,Outwater EK,et al.Uterine leiomyomas: histopathologic features,MR imaging findings,differential diagnosis, and treatment.Radiographic 1999; 19: 1179-1197.

* Correspondence to:

Ji Tan, MD

Tel: 0086-21 6270 4900

Fax: 0086-21-6270 4942

Email: ghealth2008@gmail.com