A Music Therapy Program for Women with Breast Cancer*

1 Barbara L. Wheeler, PhD . 2 Inka Weissbecker, PhD .

3 Paige Robbins Elwafi, MMT . 4 Carolina Salvador, MD

1 School of Music, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY

2 Harvard School of Public Health, Cambridge, MA

3 Cincinnati, OH

4 Department of Medical Oncology/Hematology, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY

ABSTRACT

Aims:

The primary purpose of the project was to provide music therapy services, with goals of improving mood, improving quality of life, decreasing fatigue; and gathering information on the viability of measures of these areas. It also served as a pilot project to assess the effectiveness of the procedures.

Methods:

Sixteen women were seen for music therapy, receiving from one to five sessions each. The music therapy interventions were individual sessions lasting 30-45 minutes, using live. Measures of mood, quality of life, and fatigue were taken following the intervention and at 1-month follow-up.

Results:

Results of statistical analyses as well as descriptions of the experiences of some of the patients are presented.

Conclusion:

This project provided music therapy services to women who had breast cancer. It provided information that may be useful for further treatment as well as research.

Key Words:

Music therapy; Breast cancer; Quality of life; Mood; Culture and Cancer.

Music therapy enhances complementary and integrative medical practices based on its aim to understand and integrate the physical, emotional, psychological, and spiritual aspects of the individual. Music therapy is defined by the American Music Therapy Association (AMTA) as “the clinical and evidence-based use of music interventions to accomplish individualized goals within a therapeutic relationship by a credentialed professional who has completed an approved music therapy program.”1

Music therapy has been found to be effective in treating patients with cancer. Both descriptive and experimental studies have shown promise in this area. Recent reviews include reviews of empirical data on music therapy in hospice and palliative care2 and in medical settings3 as well as two general reviews of the literature concerning music therapy in the treatment of cancer.4. 5 In addition, two meta-analyses of the medical research that have been conducted included a number of studies of the use of music and music therapy with patients with cancer.6. 7 Studies of patients with cancer have found positive results for music therapy in managing pain8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, helping with emotional and quality of life issues15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23,and alleviating the symptoms of chemotherapy24, 25, 26 and radiation.27 While not a study of patients with cancer, music has also been found to decrease fatigue after anesthesia.28 It is also possible to attend to spiritual and aesthetic preferences through the use of music that is culturally familiar.29

Patients with breast cancer frequently experience emotional distress. Women who were newly diagnosed with breast cancer were found to have high levels of distress,30 with a number of them (21%) meeting criteria for psychiatric disorders and demonstrating significant declines in daily functioning. Twenty-one percent were taking psychotropic medication. In a study of women who had undergone several forms of surgical treatment for breast cancer,31 a large percentage experienced anxiety and depression.

Quality of life issues may be related to emotional distress as well as other concerns. Patients with breast cancer have been found to have the same concerns experienced by others with cancer, including pain, fear of recurrence, and fatigue, and also some that are more specific to breast cancer, such as an altered sense of femininity, feelings of decreased attractiveness, and problems with arm swelling related to treatment. 32

Music therapy is uniquely suited to address emotional needs and support stress reduction and pain management. Music can cognitively, emotionally, aurally, and spiritually transgress the boundary of words. Music increases trust and is collaborative, making it a natural way to address patients’ emotional, quality of life, and energy needs.33 Because much of the musical experience is nonverbal, music can aid people who have difficulty expressing themselves verbally.

Cultural concerns may arise when patients with breast cancer and those who provide their care come from different cultures. It has been suggested34 that the “importance of the cultural context to health outcomes has only recently become a central concern and a part of the biomedical literature” (p.1) and that the “significance of cultural differences—its influence on the beliefs, expectations, and experiences of clinicians, significant others, and patients with cancer—in the therapeutic encounter has only recently begun to be evaluated” (p. 2). This increased awareness of the importance of cultural issues suggests the need for ways to lessen or deal with them.

Music therapy is one way to address some of the cultural differences and misunderstandings that may be exhibited during treatment for breast cancer. People reported listening to music more than any other activity over a wide variety of contexts, indicating the importance that music plays in people’s lives.35 Music can be adapted in treatment to the needs of different cultural groups. In addition, it is less stigmatizing for and more accessible to the patient who may be reticent to accept therapy due to misconceptions about treatment that stem from culture-specific or religious beliefs. Because it can be tailored to the culture of an individual, music is an ideal vehicle for helping women to feel comfortable and have their cultural needs heard. Of course, the attitude and knowledge of the music therapist about the patient’s culture are important in this sensitivity. The project called the Susan G. Komen Music Therapy Initiative was intended to provide music therapy services to women diagnosed with breast cancer who were undergoing treatment with chemotherapy/biotherapy or other therapies at a cancer treatment center. These treatments could be neoadjuvant, adjuvant, or for metastatic disease. Goals were to improve mood, improve quality of life, decrease fatigue, and to gather information on the viability of measure of these areas.

The primary purpose of the project was to provide music therapy services and address the goals as listed. It also served as a pilot project to assess the effectiveness of the procedures. The value of the project beyond the services that were provided is in the information gained about the effectiveness of the procedures and how well they were assessed. This information can be useful for others to build upon with larger projects. The study sought to determine whether women who participated in music therapy would experience (a) improved mood, (b) improved quality of life, and (c) decreased fatigue following the intervention and at 1-month follow-up.

Methods

Participants

Sixteen women were seen for music therapy, receiving from one to five sessions each. Eight women completed all five sessions, one had four sessions, three had three sessions, and two each had two and one sessions. Six of the women who completed all five sessions also completed all of the assessments. The project had been planned for 100 sessions, with 20 women receiving five sessions each, but problems recruiting and scheduling the participants led to the lower numbers.

Potential participants were suggested by a member of the interdisciplinary treatment team and contacted by the clinical coordinator for the project. Those who indicated an interest in participating were scheduled for an appointment. The music therapist or another one of the project team gave them the informed consent documents that had been approved by the University of Louisville Institutional Review Board and answered any questions prior to the patients signing the forms.

All women were being seen at the cancer center for some type of therapy, primarily chemotherapy. They had various types and levels of severity of breast cancer and were at various points in their treatment. Some were being treated for reoccurrences of cancer. Their ages were from 40 to 73 with a mean age of 55 (SD=10).

Music therapy sessions were usually scheduled when the women were already at the center for another appointment. They would generally have their appointment, then the music therapy. Sessions were held weekly when possible but were sometimes held at longer intervals, depending upon the women’s other treatments, which varied depending upon their blood counts and other factors.

Procedures

Music Therapy Sessions

The music therapy interventions were individual sessions lasting 30-45 minutes, using live interactive music. Sessions were catered to the individual needs of the patients, generally beginning by talking about how the patient was feeling, her responses to the previous session and the music to which she listened in the interim, and other issues. The music therapist would then sing and play the music the patient requested, often music that had been used in previous sessions. The patient would sometimes join in with singing, playing simple instruments, or other activity. The patient and therapist would talk about the feelings elicited in the session, often relating them to other events in the patient’s life.

The musical content of the sessions was reinforced with a CD of the music used in the session. The CD of the music was prepared by the music therapist from original and/or professional recordings available through an internet service and given to the patient at the next session, along with a CD player. Patients were asked to listen to the CD daily and keep a log of the amount of time that they listened to the music and their reactions.

Data Collection and Assessment Instruments

Patients filled out questionnaires at three intervals, at the beginning and end of the sessions and 1 month after the end of music therapy. Mood was assessed with the Profile of Mood States (POMS-SF),36, 37 quality of life with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast (FACT-B),32, 38 and fatigue with the Fatigue Symptom Inventory (FSI).39

The POMS is intended to assess transient mood states and was developed for repeated use. It includes six scales (Tension-Anxiety, Depression-Dejection, Anger-Hostility, Vigor-Activity, Fatigue-Inertia, and Confusion-Bewilderment) and a total mood disturbance score (TMD). The reliability of the POMS was originally tested on university students and patients with psychiatric problems and found to be satisfactory.36 Information on factorial and content validity of the POMS and other POMS correlates is available.37

The FACT-B is a 44 items questionnaire that includes 35 items in the FACT-General (FACT-G) and the 9 items in the Breast Cancer Subscale. It is a general quality of life scale which, together with a number of disease-specific, symptom-specific, and treatment-specific subscales, constitutes the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) scale. Reliability and validity of the FACT-B were computed with two different samples of women with breast cancer.32 Internal consistency for the FACT-B total score was found to be high (α = .90), with alpha coefficients of subscales ranging from .63 to .86. Test-retest reliability and convergent, divergent, and known groups validity were also supported.

The FSI is a 13-item self-report measure that assesses the severity, frequency, and diurnal variation of fatigue, as well as its perceived interference with quality of life. It was developed with women who were undergoing treatment for breast cancer, who had completed treatment for breast cancer, and who had no history of cancer. The seven-item interference subscale was found to have good internal consistency in all three groups of patients. Preliminary evidence of the reliability and validity of the FSI has been reported for women with breast cancer39, 40 and for men and women with a variety of cancer diagnoses. 41 Convergent/divergent validity and construct validity have been demonstrated. Test-retest reliability for the entire FSI among cancer patients undergoing treatment yielded strength of correlations ranging from 0.35 to 0.75 as assessed on three separate occasions. Overall, the FSI is established as a valid and reliable measure of fatigue in cancer patients and healthy individuals. The logs kept during the patients’ home listening experiences also were collected and analyzed according to the time spent listening.

Results

Scores on each of the subscales for the POMS, FACT-B, and FSI, given at the beginning of therapy, at the end of therapy, and 1 month later were analyzed for the six women who completed all five sessions and all of the assessments using one-way repeated measure ANOVAs. The listening logs for the home listening were also examined. Statements from the music therapist and the responses of the patients were also used to understand what occurred.

Profile of Mood States

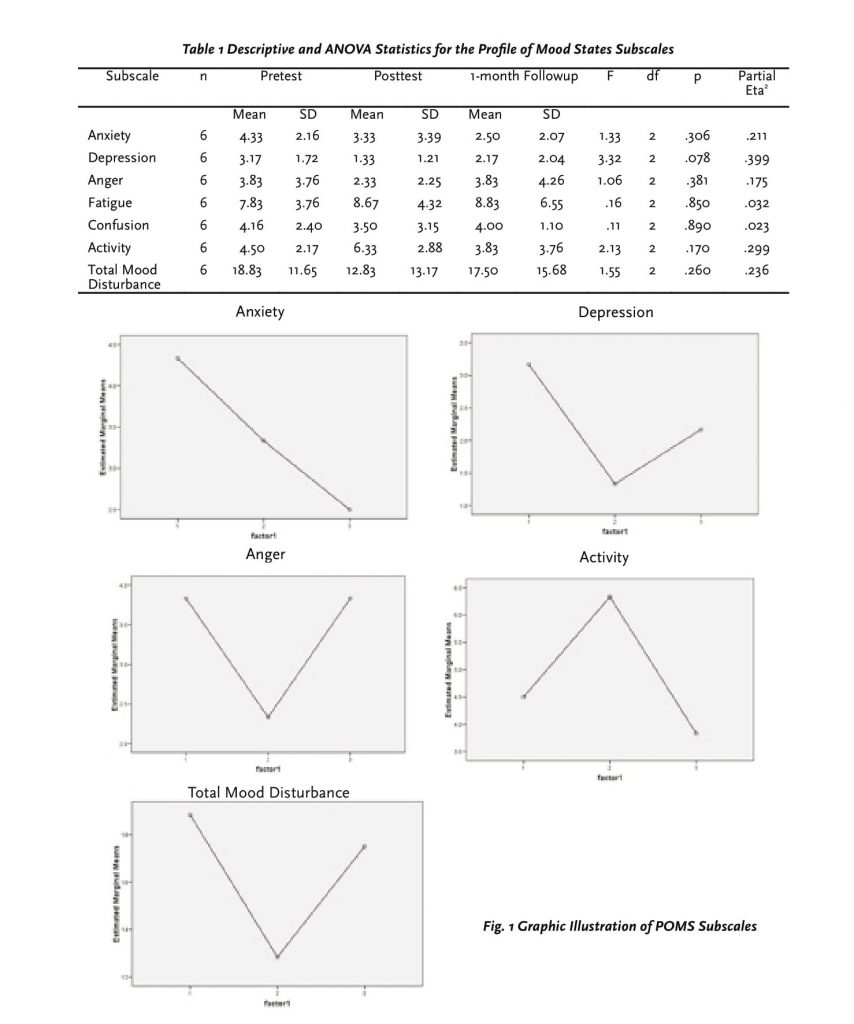

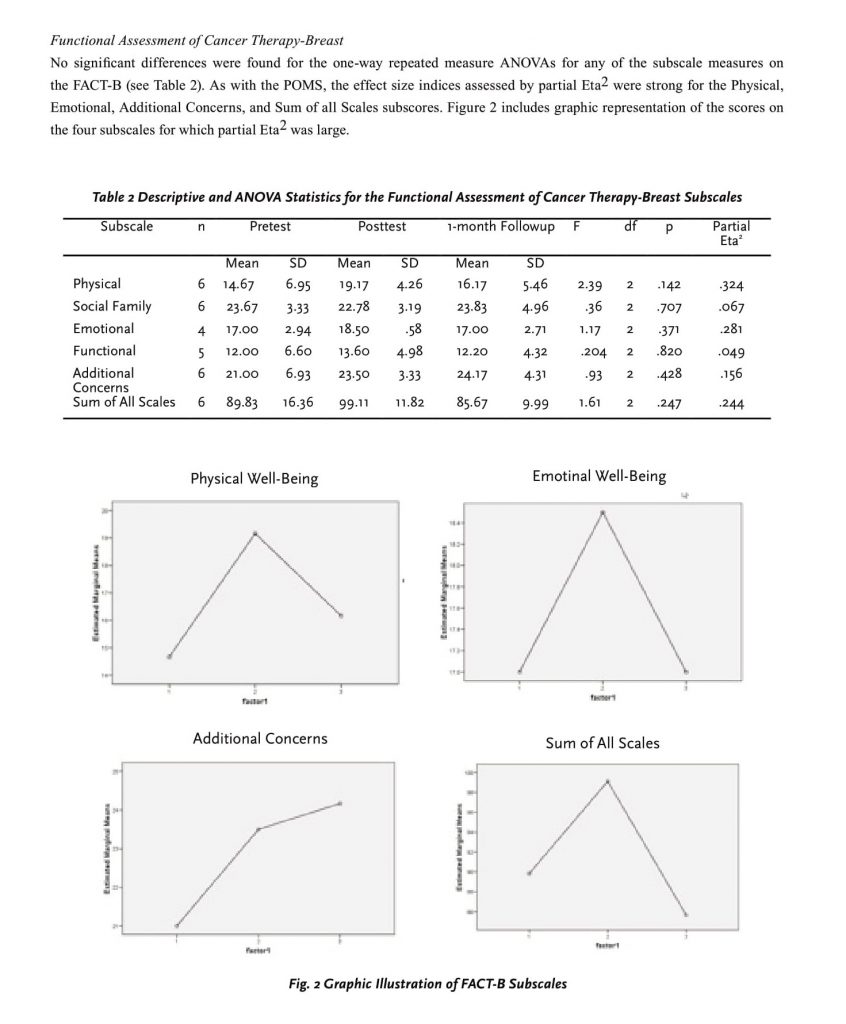

No statistically significant differences were found for the one-way repeated measure ANOVAs for any of the subscale measures of the POMS (see Table1), but a review of the mean differences revealed differences in the desired directions for all three scores for Anxiety and for the pre-to-post difference for Depression, Anger, Activity, and Total Mood Disturbance. In addition, the effect size indices (partial Eta2) for five of these subscales, Anxiety, Depression, Anger, Activity, and Total Mood Disturbance, were large. As a measure of effect size, partial Eta2 gives the proportion of total variance attributed to that factor, with values of .01, .06 and .14 indicating small, medium, and large effect size, respectively.42 Figure 1 shows graphic representation of the scores on the five subscales for which partial Eta2 was large.

Listening Logs

Eight of the 16 women filled out listening logs that tracked their listening time. The number of weeks for which they had logs varied depending upon the number of weeks of music therapy, with no log being available during the first week as they did not have a CD at that time. Of those, the mean number of days for which patients listened to the CDs was 5.0, the median was 5 days, the mode was 6 days, and the range was from 3 to 7 days. Many of the women also commented on their responses to the music on a daily basis, as was requested.

Reports from Music Therapist and Patients

The music therapist noted that many patients reported important insights during the music therapy sessions as a result of their experiences in treatment, relationships with family, and challenges of being diagnosed with cancer. While some seemed hesitant to discuss personal and family issues in music therapy sessions, others shared very personal and important information. Because patients were involved with music therapy for a maximum of five sessions, it was significant that this level of insightful discussion occurred between the therapist and the patient.

Many participants stressed how important the music was in helping them remember what it was like to feel happy and hopeful again. Some topics discussed in music therapy sessions were viewing cancer as a blessing instead of a bad experience, fighting cancer for the sake of family, memories from the past, the role of spirituality and prayer, inspiration from other cancer patients and survivors, and struggles with common side effects. A few brief summaries of some of the patients involved in the music therapy are presented below.

One patient was having a hard time adjusting to the side effects she was experiencing from the chemotherapy. She experienced extreme fatigue and exhaustion and became depressed when she would be forced to lie in bed all day. She and her husband were both musicians and he attended some of the sessions with her. He brought his guitar and played along with the therapist and the patient creating lively and energetic music. At the end of her involvement in the project, she talked about how the music therapy had extended into their personal lives, giving them increased opportunities for making and writing music together at home.

Another patient had been fighting cancer for many years and was dealing with a reoccurrence. She reported that the music assisted her with visualization and relaxation, especially at night when she had trouble sleeping. During her final music therapy session, she said that she visualized the drugs fighting the cancer and the tumors shrinking while she listened to her music CDs. Happily, she had just discovered that her tumors had actually shrunk. A third patient was an avid Motown fan. During her participation in the grant, she explored the music that she loved so much. Each session seemed to be a special time for her to explore her memories by walking down “memory lane” with the singing of each song. One day she was inspired to get up and dance around the room while the therapist sang one of her favorite songs.

A fourth patient reported feeling a lot of anxiety while she was undergoing treatment and awaiting surgery for a mastectomy. Once a music enthusiast, she had slowly stopped listening to music over the years. Towards the end of her music therapy sessions, she talked about how music had begun to be important to her again and how, with her participation in the project, she was rediscovering the music that she had once loved.

Discussion

This project provided individual music therapy sessions to 16 women who were dealing with breast cancer. The primary purpose of the project was to provide music therapy services, with goals of improving mood, improving quality of life, decreasing fatigue; and gathering information on the viability of measures of these areas. The individual sessions were catered to the needs of the women, many of whom were pleased with the program and had positive experiences. Since only six women were able to attend all five planned sessions and complete all of the assessments, only a small sample was available for analyses of progress. The statistical interpretation of the results is limited by the small sample size. In addition, many of the five planned sessions were not held on a weekly basis, as had been hoped, decreasing the possibility that effects would be seen.

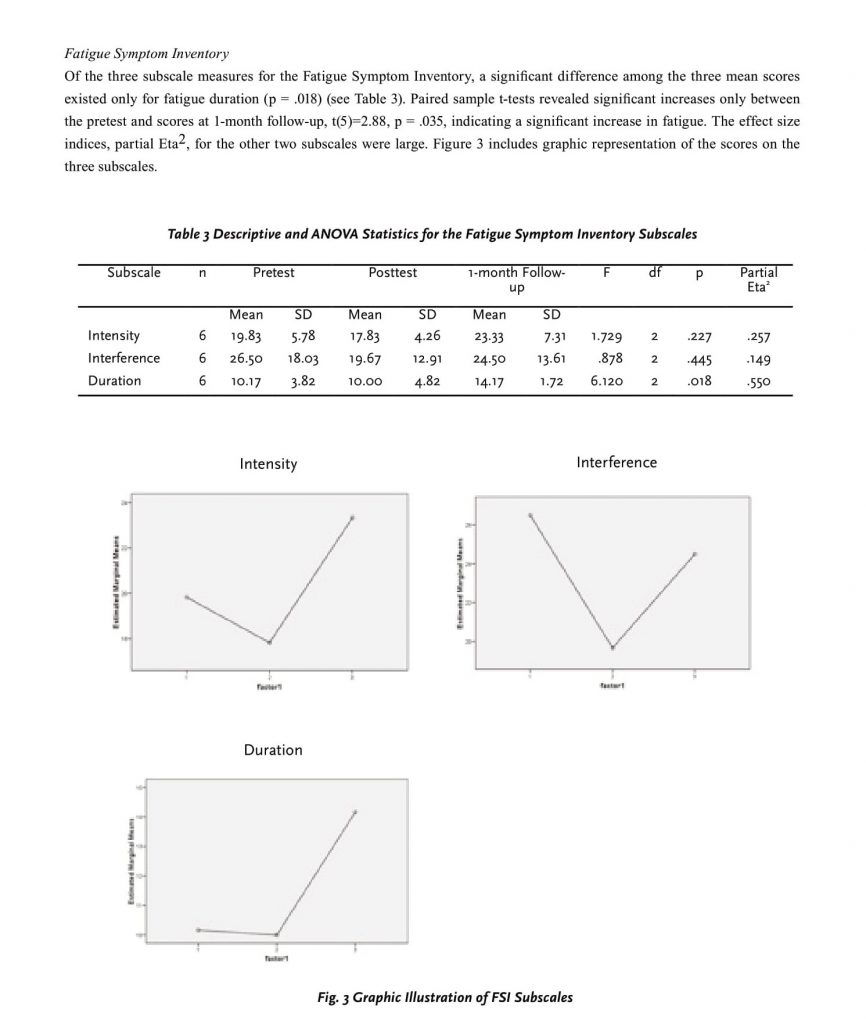

Participants were assessed for changes in mood (POMS), quality of life (FACT-B), and fatigue (FSI). Effect size indices were large for five of the POMS subscales (Anxiety, Depression, Anger, Activity, and Total Mood Disturbance) and four of the FACT-B subscales (Physical, Emotional, Additional Concerns, and Sum of all Scales). Of the three subscale measures for the Fatigue Symptom Inventory, a significant difference among the three mean scores existed for fatigue duration, with large effect sizes for the other two subscales were large. The large effect sizes suggest that a larger sample may have produced more significant changes.

The FSI subscale for duration of fatigue was the only subscale that resulted in statistically significant differences, showing an increase in fatigue from the pre-test to the 1-month follow-up scores. There are a number of reasons that the duration of fatigue could have increased. One of the more likely explanations is that the women experienced more fatigue as their chemotherapy continued and as they dealt with the continuing effects of having cancer. Since this was a treatment project, not a research study, and thus had no control group, there is no way to know whether more of an increase would have occurred among participants who received music therapy than among those who did not.

Other benefits were apparent as a result of this project. The hospital in which the music therapy took place had not had a music therapy program prior to this. Thus, part of the work of the project was to introduce music therapy to staff and patients in the units involved with the patients. This brought challenges, since medical staff members were extremely busy and were involved with the more traditional aspects of treatment. A positive result was that a bi-weekly music therapy group was initiated near the end of the grant project through the hospital’s resource center. The music therapy also offered these women validation. Sharing their music and experiences with the music therapist and then having that validated by the music therapist and through the music in the sessions and on the CD recordings was important. For many, it helped to provide important experiences, improving hope and confidence.

There were further benefits from the program, including the opportunity to explore music therapy methods appropriate for this population, piloting the measures/ assessments, collecting preliminary data, learning to work with others in the hospital and on the team including exploring possibilities for research, and helping the hospital learn about music therapy.

In conclusion, this project provided music therapy services to women who had breast cancer. It provided information that may be useful for further treatment as well as research.

References

1. American Music Therapy Association. Frequently asked questions about music therapy, 2005. Available at: http://musictherapy.org. Accessed August 21, 2008.

2. Hilliard RE. Music therapy in hospice and palliative care: a review of the empirical data. Evidence Based Complement Alternat Med. 2005; 2(2):173-178.

3. Kemper KJ, Danhauer SC. Music as therapy. South Med J. 2005;98(3):282-288.

4. Aldridge D. Music therapy references relating to cancer and palliative care. Br J Music Ther. 2003; 17(1):17-25.

5. Pothoulaki M, MacDonald R, Flowers P. Music interventions in oncology settings: A systematic literature review. Br J Music Ther. 2005; 19(2):75-83.

6. Dileo C, Bradt J. Medical Music Therapy: A Meta- Analysis & Agenda for Future Research. Cherry Hill, NJ: Jeffrey Books, 2005.

7. Standley JM. Music research in medical treatment. In: Effectiveness of Music Therapy Procedures: Documentation of Research and Clinical Practice. Silver Spring, MD: AMTA, 2000, pp. 1-64.

8. Beck SL. The therapeutic use of music for cancer-related pain. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1991; 18(8):1327-1336.

9. Boldt S. The effects of music therapy on motivation, psychological well-being, physical comfort, and exercise endurance of bone marrow transplant patients. J Music Ther. 1996; 33(3):164-188.

10. Curtis S. The effect of music on pain relief and relaxation of the terminally ill. J Music Ther. 1986; 23(1):10-24.

11. Gallagher LM, Lagman R, Walsh D, Davis MP, LeGrand SB. The clinical effects of music therapy in palliative medicine. Support Care Cancer. 2006; 14:859-866.

12. Krout R. The effects of single-session music therapy interventions on the observed and self-reported levels of pain control, physical comfort, and relaxation of hospice patients. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2001; 18(6):383-390.

13. Magill L. The use of music therapy to address the suffering in advanced cancer pain. J Palliat Care. 2001; 17(3):167-172.

14. Zimmerman L, Pozehl B., Duncan K, Schmitz R. Effects of music in patients who had chronic cancer pain. West J Nurs Res. 1989; 11(3):298-309.

15. Bailey LM. The effects of live music versus tape-recorded music on hospitalized cancer patients. Music Ther, 1983; 3(1),17-28.

16. Bonde LO. The Bonny Method of Guided Imagery and Music (BMGIM) with Cancer Survivors. A Psychosocial Study with Focus on the Influence of BMGIM on Mood and Quality of Life. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Aalborg University, Aalborg, Denmark, 2004.

17. Burns DS. The effect of the Bonny method of Guided Imagery and Music on the mood and life quality of cancer patients. J Music Ther. 2001, 38(1):51-65.

18. Burns SJ, Harbuz MS, Hucklebridge F, Bunt L. A pilot study into the therapeutic effects of music therapy at a cancer help center. Alternative Therapist. 2001, 7(1), 48-56.

19. Cassileth B, Vickers A, Magill L. Music therapy for mood disturbance during hospitalization for autologous stem cell transplantation. Cancer. 2003, 98(12):2723-2729.

20. Guangrong C, Yi Q, Peiwen L, et al. Music therapy in treatment of cancer patients. Zhongguo xin li wei sheng za zhi (Chinese Mental Health Journal). 2001,15(3):179-181.

21. Hanser S, Bauer-Wu S, Kubicek L, Healey M, Manola J, Hernandez M, Bunnell C. Effects of a music therapy intervention on quality of life and distress in women with metastatic breast cancer. J Soc Integr Oncol. 2006; 4(3):116-124.

22. Hilliard RE. The effects of music therapy on the quality and length of life of people diagnosed with terminal cancer. J Music Ther. 2003; 40(2):113-137.

23. Whittall J. The impact of music therapy in palliative care: A quantitative pilot study. In: JA Martin (Ed.), The Next Step Forward: Music Therapy with the Terminally Ill. Bronx, NY: Calvary Hospital, 1989, pp. 69-77.

24. Ezzone S, Baker C, Rosselet R, Terepka E. Music as an adjunct to antiemetic therapy. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1998, 25(9):1551-1556.

25. Frank J. The effects of music therapy and guided visual imagery on chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1985, 12(5):47-52.

26. Standley JM. Clinical applications of music and chemotherapy: The effects on nausea and emesis. Music Ther Perspect. 1992; 10(1):27-35.

27. Mowatt K. Background music during radiotherapy. Med J Aust. 1967 Jan 28, 1(4):185-186.

28. Nilsson U, Rawal N, Uneståhl LE, Zetterberg C, Unosson M. Improved recovery after music and therapeutic suggestions during general anaesthesia: A double-blind randomised controlled trial. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2001; 45(7):812-817.

29. Dileo C, Starr R. Cultural issues in music therapy at end of life. In: Dileo C and Loewy JV, editors. Music Therapy at the End of Life. Cherry Hill, NJ: Jeffrey Publications, 2005, pp. 85-93.

30. Hegel MT, Moore CP, Collins ED, Kearing S, Gillock KL, Riggs RL et al. Distress, psychiatric syndromes, and impairment of function in women with newly diagnosed breast cancer. Cancer. 2006; 107(12):2924-2931.

31. Fallowfield LJ, Hall A, Maguire GP, Baum M. Psychological outcomes of different treatment policies in women with early breast cancer outside a clinical trial. BMJ. 1990; 301:575-580.

32. Brady MJ, Cella DF, Ma F, Bonomi AE, Tulsky DS, Lloyd SR et al. Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast quality-of-life instrument. J Clinical Oncol. 1997; 15:974-986.

33. Loewy J, Stewart K. Music therapy to help traumatized children and caregivers. In: Webb, NB, editor. Mass Trauma and Violence: Helping Families and Children Cope. New York: Guilford Press, 2004, pp. 191-215.

34. Moore RJ, Spiegel D. Introduction. In: Moore, RJ and Spiegel D, editors. Cancer, Culture, and Communication. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 2004, pp. 1-11.

35. Rentfrow PJ, Goslin SD. The do re mi’s of everyday life: The structure and personality correlates of music preferences. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003; 84(6):1236-1256.

36. McNair DM, Lorr M, Droppleman LF. Manual: Profile of Mood States. San Diego, CA: Educational and Industrial Testing Service, 1971.

37. McNair DM, Heuchert JP. Profile of Mood States: Technical Update. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi- Health Systems, 2005.

38. Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E, Bonaomi M et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Scale: Development and validation of the general measure. J Clinical Oncol. 1993; 11(3):570-579.

39. Hann DM, Jacobsen PB, Azzarello LM, Martin SC, Curran SL, Fields KK, et al. Measurement of fatigue in cancer patients: development and validation of the Fatigue Symptom Inventory. Qual Life Res. 1998 May;7(4):301-310.

40. Jacobsen PB, Hann DM, Azzarello LM, Horton J, Balducci L, Lyman GH. Fatigue in women receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer: characteristics, course, and correlates. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999, Oct;18(4):233-242.

41. Hann DM, Denniston MM, Baker F. Measurement of fatigue in cancer patients: further validation of the Fatigue Symptom Inventory. Qual Life Res. 2000; 9(7):847-854.

42. Green SB, Salkind NJ, Akey TM. Using SPSS for Windows: Analyzing and Understanding Data. 3rd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 2003.

1Thank you to Gene Ann Behrens, who provided additional assistance with the statistical analysis and interpretation. * This project was funded by Susan G. Komen for the Cure, the Louisville, KY, local chapter of the Susan G. Komen Foundation.